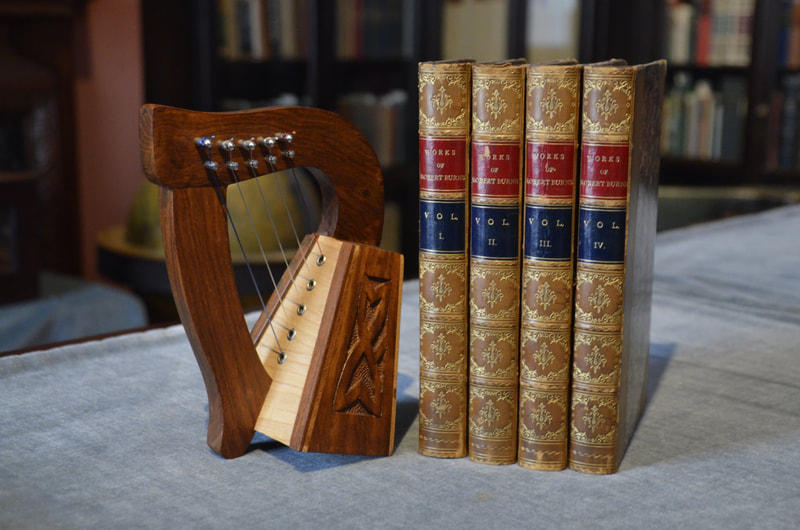

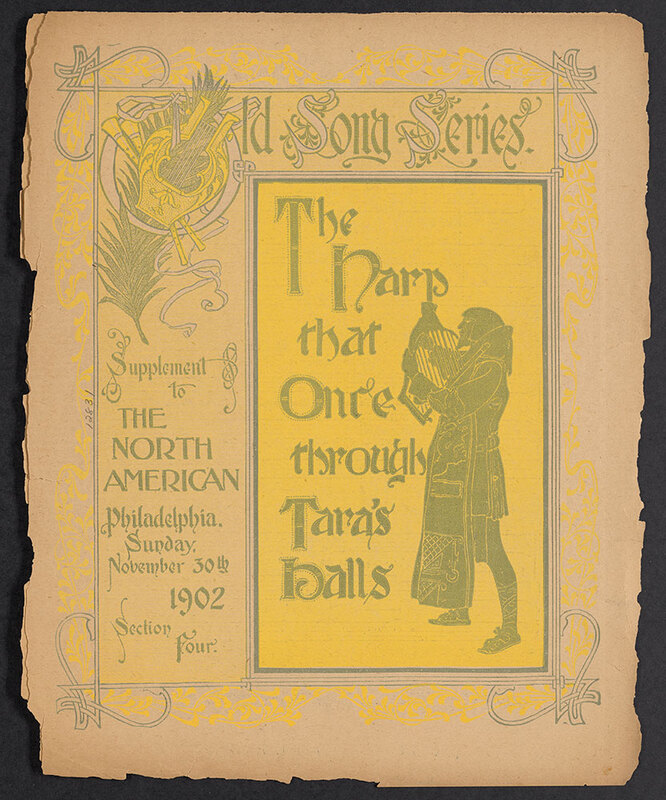

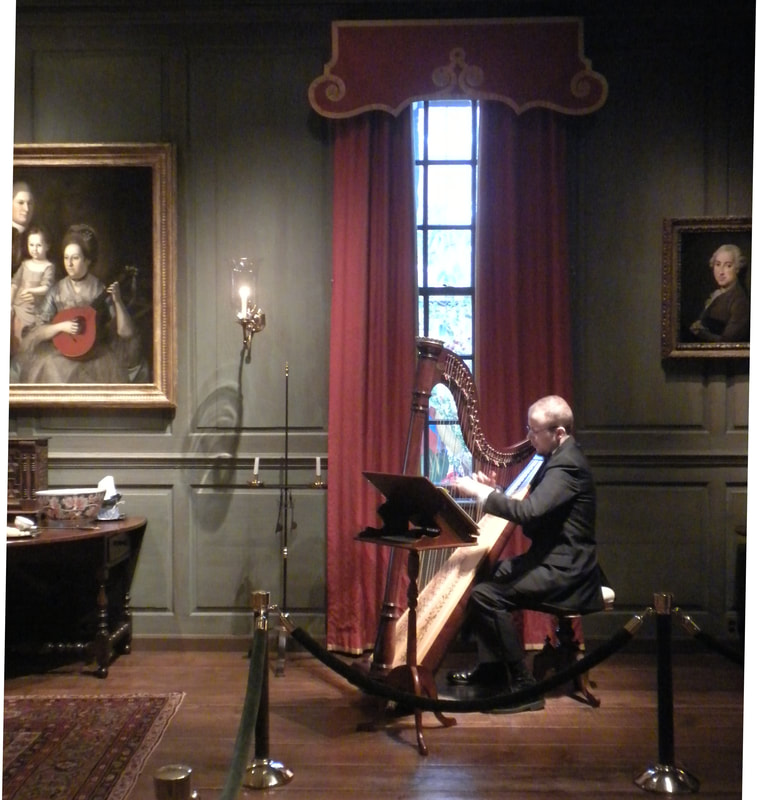

"Biblioharp" is the interpretation of rare books and

manuscripts through harp music.

|

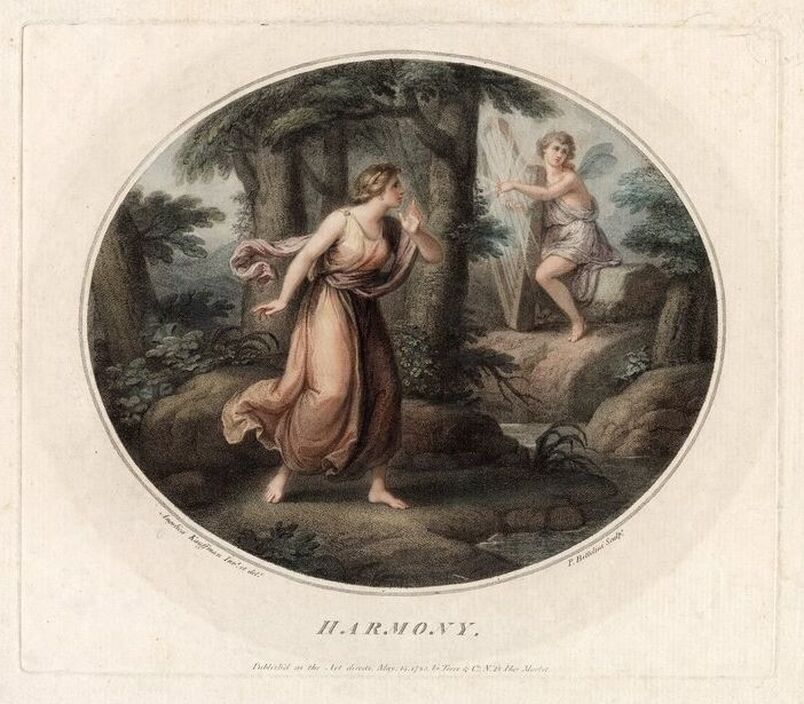

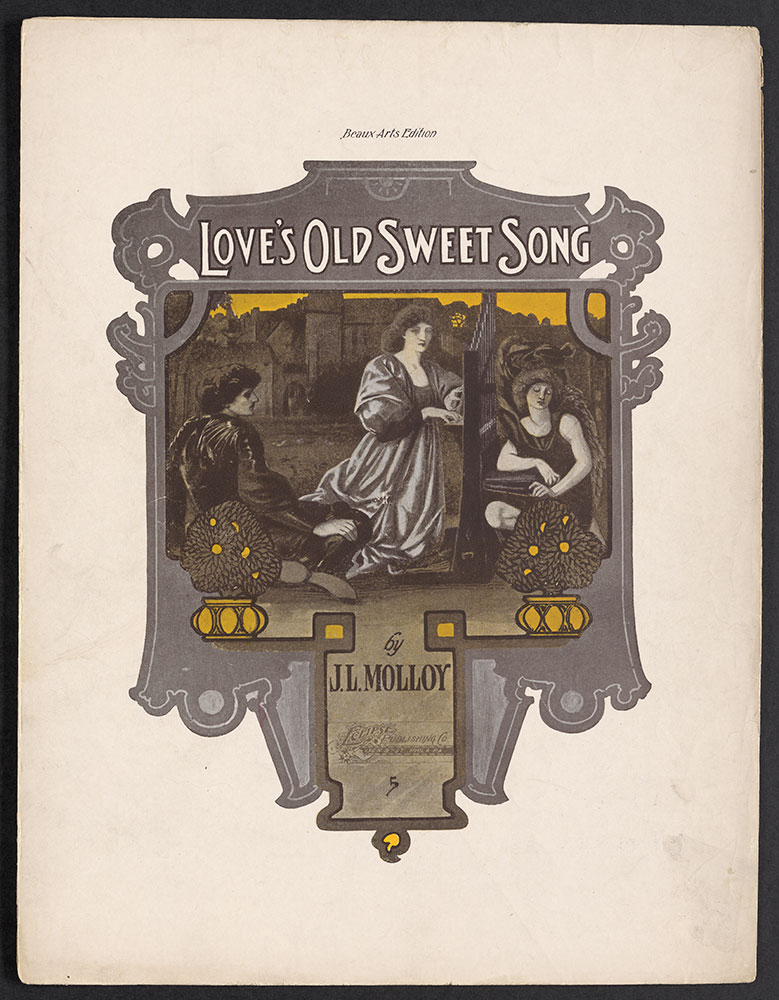

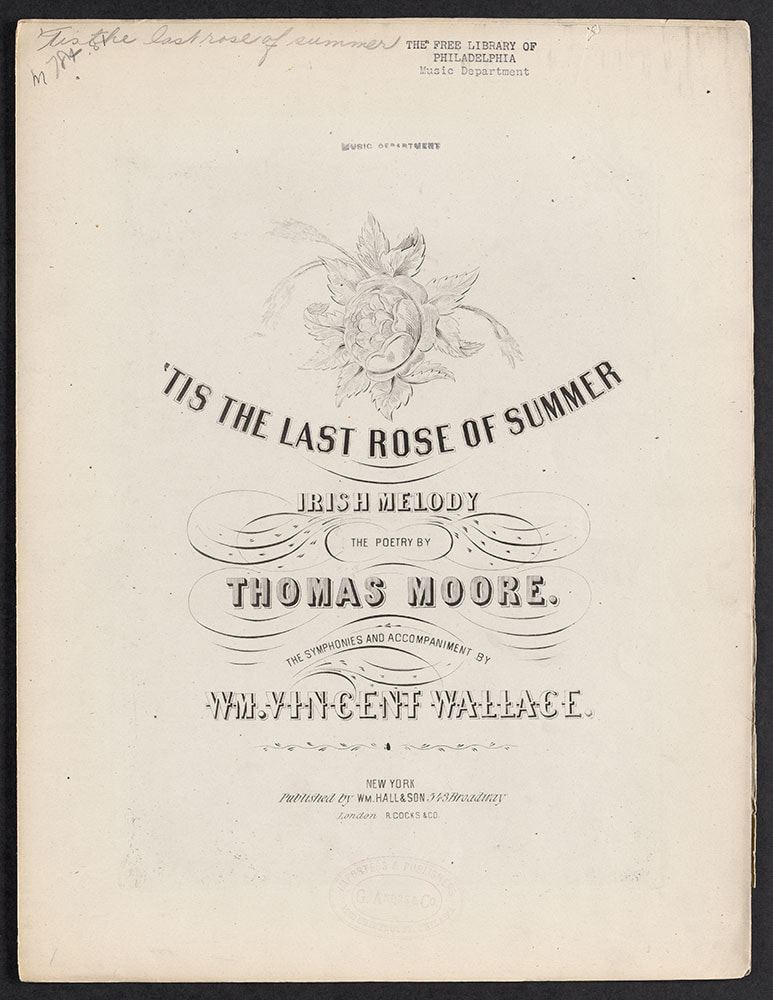

The boundaries between the arts (music, literature, and various visual media) are thin, and often fluid. Biblioharp encourages exploration of rare books and manuscripts through music.

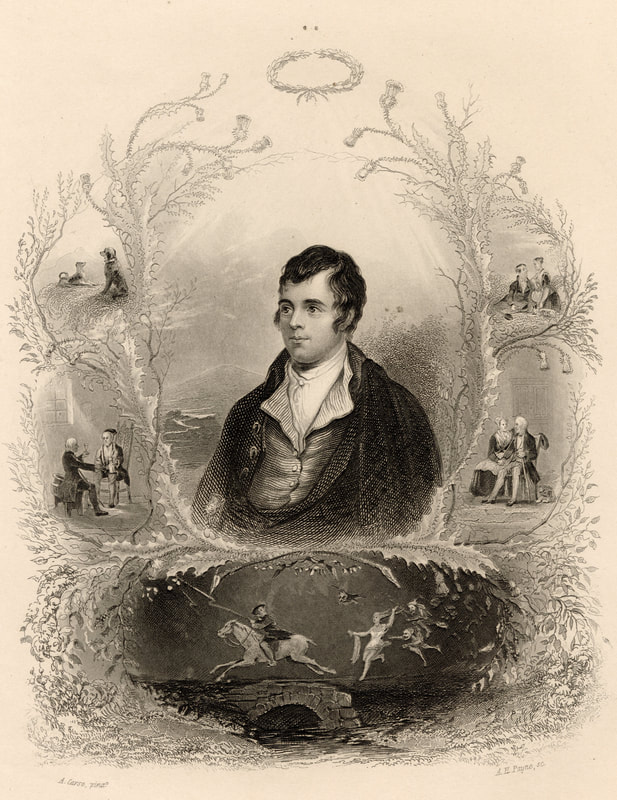

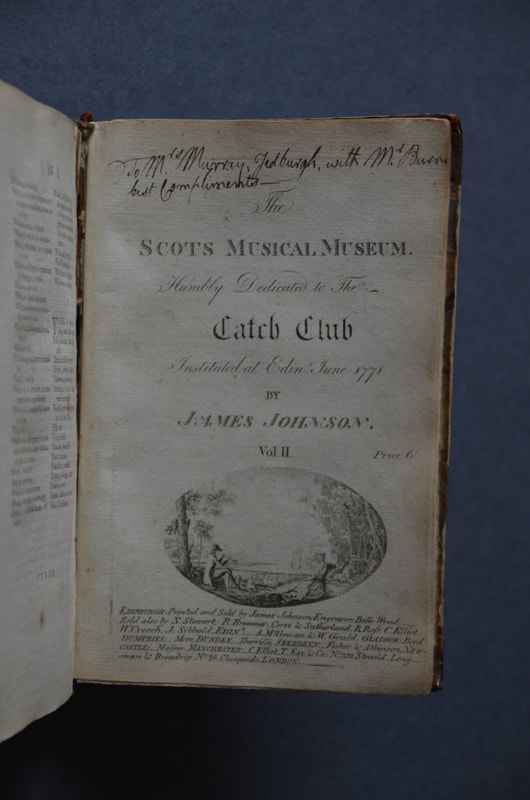

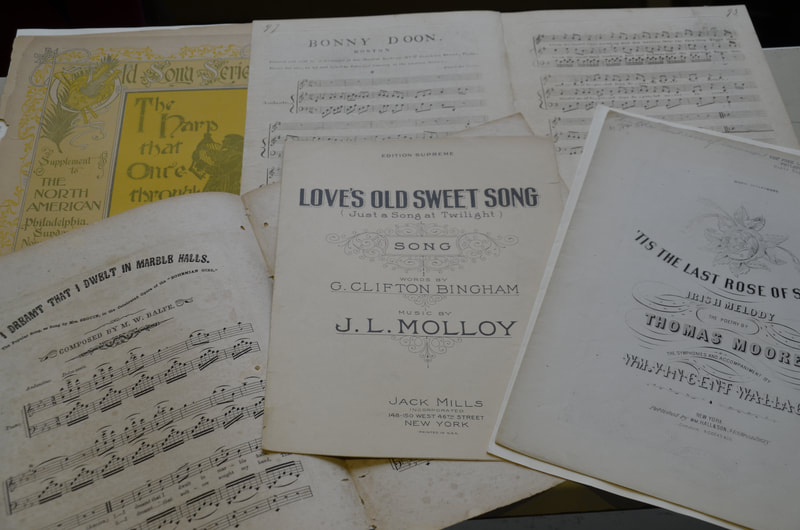

Music has played a key role in social and cultural history, and many great works of poetry and prose literature are best understood within the musical context of which they were a part. For example, much of Robert Burns's poetry was written to be sung, and the great Irish author James Joyce makes frequent references to Irish music in Ulysses, Dubliners, and his other works. What is more, the visual arts often reference the performance of music, making sound a key element in interpreting paintings, prints, sculptures, and other media. Biblioharp is a strategy I have developed to bring historical topics and literary masterpieces to life by resurrecting, to the extent I am able, the musical worlds with which they are associated, and inviting audience members to engage multiple senses in understanding material texts. |

“To speak in the poetical language of my country, the seat of the Celtic Muse is in the mist of the secret and solitary hill, and her voice in the murmur of the mountain stream. He who woos her must love the barren rock more than the fertile valley, and the solitude of the desert better than the festivity of the hall. … A few irregular strains introduced a prelude of a wild and peculiar tone, which harmonised well with the distant waterfall, and the soft sigh of the evening breeze in the rustling leaves of an aspen, which overhung the seat of the fair harpress.”

Sir Walter Scott, Waverley; or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since, 1814